* This article was published in the 40th print issue of HUFS Alli, “Twist the Perspective,” in August 2025.

Pitch-black darkness swallowed the hospital ward. From the far end of the corridor came the thud of boots, curt orders slicing through the air. Soldiers were moving toward the military base next door. It was the spring of 2014, and she lay in a hospital bed.

The next morning was not the same as the one before. Outside of her window, strange flags fluttered above rows of military vehicles. She was no longer in Ukraine, but in Russia.

Her name is Ness. Born in Ukraine, raised in Crimea. But from that day on, her nationality shifted—Ukrainian one moment, Russian the next.

Still, she insists:

“I am Ukrainian”

That night, she realized a single yet painful truth: nationality can be changed far more easily than identity.

A Child of the Sea

War. The word alone feels unbearably heavy. Yet when the door opened, a young woman with red hair, pale skin, and a radiant smile walked in—as if she carried none of that weight.

“Where should I look for the camera?”

She asked with a laugh. That was the first thing Ness, a 26-year-old student of English Literature and Culture—said when we met. As she adjusted her gaze toward the lens, jokes and laughter filled the room.

Her passport still bears the words:

‘Born in Ukraine’

She was born in western Ukraine, near the Polish border—a place many call the most quintessentially Ukrainian part of the country. But when her parents moved to Crimea for work, her childhood took root there completely.

She grew up with the sea. The city’s edge was a shoreline, and when she opened the window, waves were the natural soundtrack of her days. Feodosia, on the southeastern tip of Crimea, was where she called home—a peninsula wrapped on three sides by water. Summers brought floods of tourists; every alley was lined with guesthouses and souvenir stalls. Her parents made maps of the city and ran a small publishing house for guidebooks. Her mother was an artist, and her father a technician.

“Every summer, the whole family threw ourselves into the publishing work,” she recalled. “Hand-drawn streets, hand-drawn houses…”

As she described the scent of salt and the breeze of the water, her voice caught. For a moment, she seemed on the verge of tears. Perhaps the smile she had shown earlier was less joy than armor, a way to keep heavier feelings at bay.

From the age of seven, she learned how to fold papers, stack cards, and bind maps. The city maps hand-drawn by her mother can still be found on the internet. But her happiest days came in September, when the tourists were gone. The sea grew quiet again, as if its true owners had finally returned. Those were the days when her parents, her sister, grandmother, and the family dogs would drive out to a small village. On hidden beaches untouched by visitors, they spent entire days swimming together, ending with laughter in the car, their hair still wet from the saltwater. That sea now lives only in the photographs.

“It’s been more than six years since the last time I went home”

She still thinks of those waters. And then, almost in a whisper, added:

“But for now… I don’t want to go back there yet”

One Morning, It Was Russia

She was fifteen that spring, hospitalized with a lung infection. Politics, armies, and war still felt like distant concerns, far from her world. But one night, the entire hospital went dark.

“From that day on, we began to feel the war,” she recalled. Strange uniforms appeared on the streets. At school, the flag above the classroom changed. Currency shifted, language changed, and her plans for university grew hazy. Fear settled into her life, little by little, until it became part of her daily existence. “The day before, I was living in my country. The next morning, I wasn’t.”

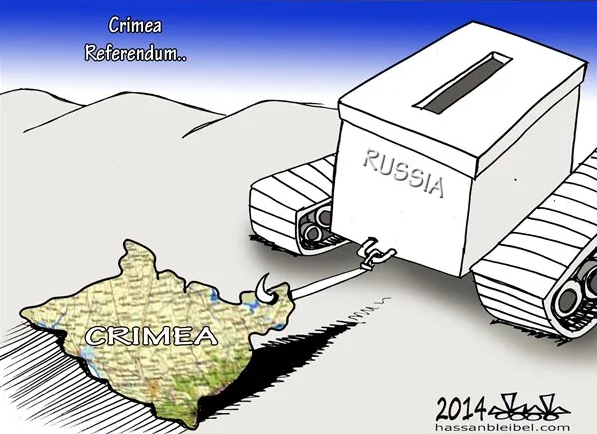

What struck her the most was the silence. No one asked. The referendum on Russia’s annexation of Crimea was a mere formality, a performance without real choice. Some even believed it was for the best—that if Russia hadn’t come, the war that erupted in Donetsk and Luhansk in 2014 would have consumed Crimea too.

Now, more than a decade has passed, Ness says that most people in Crimea tend to avoid the subject altogether. “What’s the point of talking about it anymore?” has become a common refrain. Yet Ness, along with many in Crimea, still thinks this way:

“I was born and raised in one country. Then one day, I woke up a citizen of another country. The annexation was forced upon us, and no one ever asked”*

* In 2014, Russia annexed Crimea, a region that had been part of Ukraine. Moscow justified the move as an effort to protect ethnic Russians after the change of government in Kyiv. Since then, Crimea has been treated as Russian territory.

Collapsed Classrooms, Vanished Dreams

Even after the power returned and the soldiers withdrew, life never went back to how it was before. Overnight, the flag above the blackboard has changed. New textbooks appeared on students’ desks. Exam subjects were rewritten, and the questions were no longer Ukrainian.

Ness loved literature. She had been writing short pieces since middle school, and by the time she entered high school, she was preparing to study literature, Ukrainian, and English at university. But after the annexation, every plan collapsed.

“It was like telling a Korean student who has spent years preparing for the national college exam to suddenly take China’s college entrance exam instead”

The language changed. Ukrainian literature exams were replaced with Russian ones. She had to learn subjects she had never studied, starting from scratch. The teachers she knew were gone, and those who remained now gave instructions in a different tongue.

It wasn’t only the schools that had changed. Universities, administration, even the way people looked at her shifted. Ukrainian institutions closed their doors to Crimean students. Russian universities, meanwhile, offered nothing but indifference: “If you pass, you come. If not, too bad.” She became a person without a place.

Still, she sat the exams. To pay tuition, she took up part-time jobs. Her mother fell ill, and Ness closed her textbooks to become her caregiver. The world that landed on her desk was far too heavy for a teenage girl—but it arrived all the same, without apology.

What Is a Nation?

On her very first day in Korea, she thought to herself: “Maybe life can be livable here.” When she wheeled her suitcase out of the airport, the sky was clear and the streets were calm. There were no soldiers, no police, no checkpoints. The city was strange and complicated, but it did not feel threatening.

People were absorbed in their own lives. No one asked about her identity, her nationality, or where she was from. It was an ordinary peace she had never once experienced in Crimea. What Seoul gave her was safety. Yet that safety felt like a peace borrowed only for a while. On some days, even the sound of a plane passing overhead filled her with dread. On Jeju Island, the smell of the sea reminded her so sharply of home that she broke into tears.

“For the first time, I felt that this place could also be home. But even then… I felt guilty. Because my family was still there, and I was the only one who was safe. (…) If you ask people from the former Soviet countries what they love most about Korea, I think everyone will say the same thing: safety. For me, too, that was the first”

But safety alone was not enough. Ness has been able to continue her studies in Korea thanks to scholarships that support students in financial hardship. It was society sharing the cost of an education too heavy to carry alone. Even so, she works in three different jobs to cover her living expenses. Watching her bank balance shrink, she constantly weighs rent against the donations she still insists on sending home. “The hardest part, without question, was money. I have to survive completely on my own.”

In the early months of the war, she supported President Volodymyr Zelensky. “The way he wore a uniform and filmed himself in the city left an impression. He wasn’t just sitting in an office like Putin.” But as time passed, her view changed. She believes he missed multiple chances to end the war—or at least to negotiate a ceasefire. “He should have tried dialogue as well as a military response. But there was never such an attempt.”

“My sister and her friends had to pool money to buy my brother a bulletproof vest. The government didn’t give him one. How can that make sense?”

Allegations that Western weapons never reached the front lines, that the war itself had become profitable for the government, and the relentless toll of human sacrifice left her disillusioned. “Now I don’t see him positively. The most important duty of a president is to protect the well-being of the people. And I don’t think he has done that.”

So what, then, is a nation—for her, and for us? The economist Adam Smith, in The Wealth of Nations, defined the duties of the state in this way.

"First, to protect society from the violence and invasion of other nations, by maintaining arme

d forces.

Second, to protect every member of society from injustice or oppression by establishing an ex

act administration of justice.

Third, to erect and maintain public institutions and works that, though beneficial to the whole

society, are of such a nature that the profit could never repay the expense for any indivi

dual."*

* Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, Book V, Chapter I

Her story reminds us that the true reason for a nation’s existence is not an abstract idea, but something that shapes the everyday lives we all share.

February 2022: When Fear Returned

She can’t quite remember how she first heard the news. What she does recall is that her friends began to send frantic messages: “Something’s happening.” It was morning in Korea, but night in Ukraine. Ness immediately called her sister but there was no answer. Panic set in.

After two months without smoking, she lit a cigarette again and sat in the doorway, chain-smoking for hours while glued to the news. Headlines poured in: cities bombed, military bases and airports under attack. She opened more than ten news sites at once, then turned to Twitter, searching for posts from ordinary people—because she no longer trusted the reality in the media.

She kept calling her family in Crimea. “Are you safe? Are you okay?” The thoughts of them—and of her friends back home—have never left her mind. It felt as if her own body was collapsing. That day, Vladimir Putin delivered a “special address.” Moments later, the invasion began. A friend sent her a video clip asking, “What on earth is he saying?” Ness replied, “I don’t know. Has he gone mad?” Putin spoke of Ukraine’s “denazification” and “freedom,” but to her, none of it made any sense. She had never imagined something like this could happen in the 21st century—let alone between neighboring countries.

But she also knew that the war hadn’t truly begun in 2022. It had started in 2014, in Donbas, and had dragged on for eight long years. Now, the entire nation has become a battlefield.

That day, her thoughts clung solely to the people there. Checking her bank balance, she urged her sister: “Take the car, grab the papers, and head to the border. It’s far to Poland, but you need to leave now”

Her sister’s reply was firm: “It’s too late. The road between our city and the next has already been bombed. If we try to leave, it will be worse—we’ll be hit by bullets or by shells.” In that moment, even from Korea, Ness felt the terror seep directly into her body.

“It was terrifying. I was just watching the news, but it felt as if I were right there, living it”

Why the Windows Stay Broken

When the war began, Ness’s older brother went to the front. He had served before in Donbas and left a single line: “I can’t stay home. There are too many people to protect” The moment he reached the front line, he called his sister to give his location. Over the speakerphone came the sounds of bombardment—gunfire, explosions, even human screams.

Ness does not chat with her brother often. Like many siblings, their relationship is distant; their large age gap means they rarely spend time together. “When he was sixteen, I was only four,” she said. However, it was his story that brought her closest to tears throughout the interview. These days, she hears from him perhaps once every week or two, just a brief message: “I’m alive. I’m okay”

With her sister, the contact is daily. During video calls, Ness has heard the roar of planes and the crack of explosions through the window. Once, the power cut mid-conversation. At six in the morning in Seoul, as she was getting ready for class, her sister texted: “There was a strike near our house. I’m sitting in the hallway with the cat, far from the windows”

One blast shattered every pane of glass in her sister’s apartment. Three years later, the windows remain unrepaired.

“There’s no point in fixing them. They’ll shatter again”, said her sister.

That is the reality of war. Ness’s sister and brother-in-law live close to the front, continuing their work as best they can. He repairs military vehicles; she works for a charity helping refugees and the wounded. The dog and cat they adopted during the war have become family too.

Their conversations are not filled with war alone. “If I die, I die. If not, I go back to work,” her sister once told her—a phrase heavy with exhaustion, but also with resilience. Like the broken windows, their days could collapse at any moment. And yet, through the cracks, they let in light and air and carry on living.

The Reality Missing From the News

What Ness saw with her own eyes was nothing like what she read in the news. “Everything. Honestly, everything was different,” she said. She followed Russian, Ukrainian, and international outlets alike, but none told the full story. Each showed only one angle. Russian news, in particular, bordered on propaganda—repeating, “Russia is winning,” even as Ukrainian forces pushed them back on the ground.

That is why she came to trust the posts ordinary people shared on X, formerly Twitter. “There was a strike near me”—such immediate fragments, with photos and shaky videos attached, felt more real than any polished report.

Media coverage, she noted, focused almost entirely on military maneuvers and battlefield gains. What she wanted to know were the stories of families, civilians, the ordinary people still clinging to life amid the rubble. Headlines like “Our army pushed 200 meters forward” meant little compared with the voices of those who had lost their homes and were still carrying on.

Countless stories remained unshared. No outlet could record every bombing, every death, every building reduced to dust. Too many things were simply erased. Her sister once told her about the city’s sports complex, a public facility with a gym and swimming pool. It had been bombed four separate times, yet never closed. Workers patched the windows with plywood and carried on. Such details never made the news.

To Ness, these vanishing fragments are the truest reality. The small, relentless bombardments. The injuries. The daily ruptures of ordinary life. These are the real weights people are enduring. Journalism has rarely captured those voices. That is why she has chosen to speak. Because if no one tells it, this reality will cease to exist. And she knows so well about what silence truly feels like—she lived in it during her years studying in Moscow, where the void of truth pressed down on her like a weight.

Friends Behind Bars

After the annexation of Crimea, Ness spent several years studying in Moscow. What she encountered there was isolation—absolute and suffocating. No one around her wanted to hear her thoughts. On state television, the voices of Crimea had been erased. “There were moments when I wanted to jump out of a building,” she admitted. “I had no one I could share my thoughts with”

In Moscow, she majored in journalism. It gave her a front-row seat to how the media really worked—and how propaganda spreads. During a brief stint at a Russian state broadcaster, she witnessed stories being rewritten, uncomfortable truths cut out in real time. “I realized if I stayed in Russia as a journalist, it would kill me,” she said. From that day forward, she knew she could no longer remain.

Some of her colleagues never escaped. “A few have been killed. Others are serving prison sentences in Russia,” she said. Their crime was calling the war by its real name. In today’s Russia, it is illegal to describe the invasion of Ukraine as a 'war'. To do so publicly can land a person in prison. The state enforces a single phrase instead: 'special military operation'.

I Am Both Crimean and Ukrainian

“Where are you from?” It is the question Ness hears most often in unfamiliar places. And she always answers in the same way:

“From Crimea” Then, after a short pause, she adds:

“I am Ukrainian”

For her, nationality is not a bureaucratic formality. It is language, memory, childhood, and the texture of family life. At home, she spoke Ukrainian with her mother. At school, almost every subject was taught in Ukrainian. Russian was just another foreign language, appearing once a week in class.

But when street signs were changed, when textbooks were replaced, when the line in her passport was rewritten, she realized something important for the first time: that a single political decision could shatter a person’s identity.

People of Crimea often prefer to call themselves neither Ukrainian nor Russian, but Crimeans. It is a land layered with invasions and returns—once Greek, later a Roman colony, part of the Ottoman Empire, then the Soviet Union. A territory marked by conquest and extraction. That history has left identities adrift.

In Russia, voices that did not fit the state’s narrative were branded as “foreign agents.” In mainland Ukraine, those from Crimea were sometimes treated as belonging to a “gray zone.” Even saying the name of her hometown required an explanation: “It’s now said to be Russian territory, but I grew up there as a Ukrainian”

And so, to this day, she repeats the same sentence—hoping that someday it will stand on its own, without explanation:

“I am both Crimean and Ukrainian”

Fireworks, Not Firepower

When asked what she would do first if the war ended, Ness smiled faintly. “Fireworks. I’ll set off fireworks” Explosions of joy in the sky. Bright sounds that paint the night above. For her, it would not be a mere celebration, but a ritual only the survivors could perform—small and yet immense.

And then, she admitted that she would probably cry. She has always been quick to tears, and she knows that when the reality of peace finally sinks in, she will collapse into them.

“I think I’ll cry a lot. On video, of course”

She believes this war can have no winners. Too much has been lost; too many names have disappeared. But survival itself, she says, is enough. Her dream is simple: to return one day with her family to Crimea. It doesn’t matter what flag flies over that land. What matters is showing her children the sea where she grew up.

“That little city, the sea so clear that few people know it. I want to walk again on that beach where I was raised—together, with my whole family”

Ness waits for the day of fireworks. She imagines the night when she can finally sleep without worry. A night when she no longer needs to check for a message from her brother or her sister saying they are safe. A night with no missiles, no air raids—only a wide, quiet sky above.

Do Not Forget Us

Ness lives each day with a sense of guilt. While she has three meals a day and sleeps safely in Korea, her brother holds a rifle on the front line, and her sister endures nights beneath shattered windows..

Every morning, her day begins with messages: “Are you okay?” “Was it quiet today?” “Has the power come back yet?” The questions seem ordinary, but for her, they are proof of survival—signs her family has made it through another day.

She longs for the war to end. However, she knows that alone will not be enough. Real peace, for her, is far simpler: a day when nothing happens under the open sky. A day without gunfire. A day without news of bombings. A day when people no longer hold their breath to survive. Peace, she says, is when family is alive, when you can sleep through the night, when there is food on the table, when you can stroke the cat. “That is peace. A blue sky, and a quiet day”

She knows peace is not something handed down by others, not something won on someone else’s battlefield. That is why she keeps speaking, keeps recording, keeps reaching out. She wants to remember the names of those who vanished while raising their voices—whether in Ukraine, in Russia, or anywhere in the world—against war and authoritarian power.

That, too, is why she chose to tell her story: so that people are not remembered only as casualty numbers. Wars may be launched by governments, but it is people who fight, who survive, who weep and laugh, who protect one another. That was the truth she wanted us to carry to the end.

And at the end of our conversation, she made a quiet plea:

“Do not forget us. And do not forget the people beside you either. Because in every war, at its beginning and at its end, there are always people”

김명휘 기자(kimjack7@naver.com)

허부현 기자(beee0804@naver.com)